Life

In a cupboard there is an album containing photographs depicting three generations. One picture shows people grouped around a man of about 60 who is holding the hands of the two women next to him. In front of him three young women are sitting in the grass, one of whom appears again in the second picture. She might be around 18 years old. Is she standing next to her future husband? She looks as if she were in love. Then a picture of a boy sitting in an armchair with a baby, laughing. The boy looks at the camera, the baby in another direction. Maybe someone is making a joke to get them both to smile.

Facts

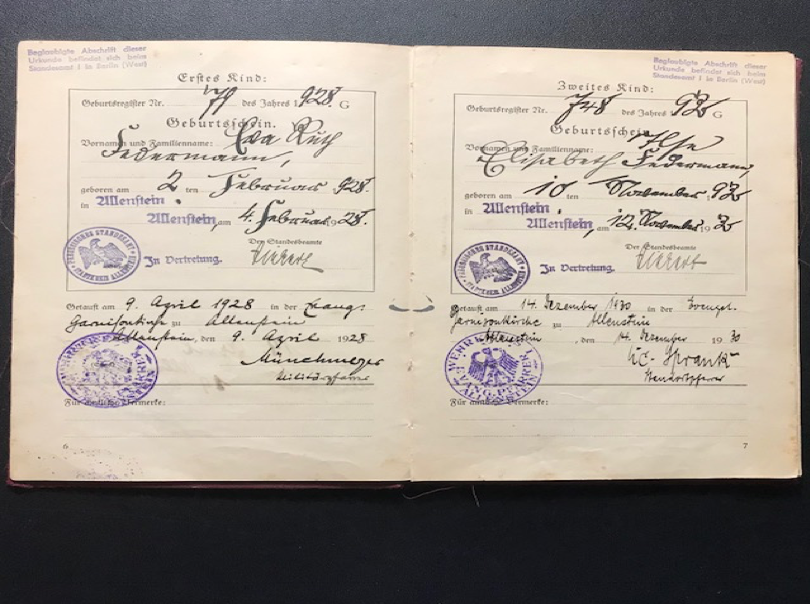

Life offers data. It is administered, recorded. My grandfather was born in 1900 and died in 1973; my father was born in 1913 and died in 1975; my mother was born in 1930 and died in 2018. They all lived through and suffered from World War II, my grandfather and father as soldiers fighting in Hitler’s Wehrmacht, my mother as a refugee. In the box, where also the photo album is kept, the family register (“Familienbuch”), with birth, marriage, and death certificates, continues to record these dates.

A child is delivered by caesarean section. A bloody affair. It is asleep when it is taken out of its mother’s womb. The surgeon gives it a slap. It wakes up and screams. It is placed in its mother’s arms.

I remember my father’s death well. He was in a coma, breathing heavily. Then he woke up once more, was without the fear that had plagued him before, said a kind goodbye to everyone and died. I regret that I was not there when my mother died. A few weeks before she died, I was still pushing her in her wheelchair along a forest path behind her nursing home. Afterwards we bought ice cream and ate it sitting in the sun in front of the Italian ice cream parlor.

We come into the world, breathe, drink, eat, urinate, defecate, sleep, dream and wake up, love and hate, get sick and get well, and, at some point, we die and are burned or buried in the ground.

Sense

Biology explains what happens when we breathe, drink, eat, metabolize, procreate, and die. But these processes are not merely biological facts, because we also actually experience them. Everything that we find beautiful and ugly, that pleases and frightens us, happens in this flow of experiences that makes up our lives. In 1977, Wolf Biermann wrote the poem Was this it? (“Das kann doch nicht alles gewesen sein”) about exactly this stream of experience:

Was this it?

A couple of Sundays and children bawling

It must still lead somewhere

Overtime, some gravel

And in the evening TV is paradise

How could I see any meaning in this?

So this was it.

There is still something left to come, right?

There must be more life to life – right.

Hey, buddy, where is the fun in all of this?

Just work and grind and cough and hurry

And then kick the bucket? – right.

So this was it.

Some soccer and a driver’s license

So this was the so called thunderous life – right.

I would like to see more things colored blue

And I want to drive some laps that are square

And only then I shall kick the bucket… right…

(Transl. by ES.)

In the poem, “meaning” is mentioned: life should have a meaning. What could that imply? Should it point to a goal—a different one from the end goal death—an achievement, a certain success? Is it meant to refer, like a text, to something other than itself? Perhaps it seems like a story to us. For we can, after all, tell of our lives, and when we have grown old, we can tell our lives. So is it a story with a moral? In 1918 Wittgenstein wrote the following lines on this subject in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus:

“6.52 We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all. Of course there is then no question left, and just this is the answer.

6.521 The solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of this problem.

(Is not this the reason why men to whom after long doubting the sense of life became clear, could not then say wherein this sense consisted?)”

If we were to think of life as a riddle to be solved, or a story with a meaning beyond itself, as a journey with a clear destination, then perhaps life would constantly disappoint us. For all answers to the supposed riddles of life, all statements of purpose and all goals, seem shallow and trivial to us. Does Wittgenstein mean that a meaningful life is lived by those who no longer conceive of it as a riddle to be solved, as a story that amounts to something? But how can this be accomplished? Or is the idea false that “something”— life – right?— must succeed in order for it to be “meaningful”? Gymnastic exercises and circus performances can succeed, but life? Did Einstein succeed in life—did the mass murderer Fritz Hamann fail in his? Did Jesus and Socrates, who were sentenced to death, succeed in their lives?

Assessments

We judge other people’s lives, and perhaps we will judge our own life when we die. But from which point of view do we do that and based on which benchmark? The standards of a young girl are different from those of a mature woman, and those of an old woman are different yet again. In which perspective does life appear as it “really” was?

We cannot look at our lives from the outside, as Cambridge philosopher Raymond Geuss rightly pointed out in his 2020 book Who needs a World-View?. We cannot know what it felt like for Einstein, Hamann, Socrates, and Jesus, respectively, to live their lives. Which is why we cannot judge other people’s lives. We can say that Einstein was kind and highly instructive to his fellows, that Fritz Hamann was a dangerous and cruel man, and that Socrates and Jesus were wise. But does that mean they succeeded or failed in life? Few of us are physical geniuses, or mass murderers, nor are we wise. Does it matter how others judge our life?

Most of us also live for others: for those we love, for those we care for. Some live against others when they loathe and fight. But are these the criteria which give meaning to life? Does life gain meaning from great love or from caring for one’s children? Did the battle that the Allied soldiers fought and won against Hitler’s Germany in Europe give meaning to their lives? Are the lives of those who have not experienced great love, who do not have children, who do not fight battles, nor lose them, or who fight “on the wrong side”, meaningless? Wouldn’t it be oddly arrogant to claim that?

MH, Zürich 2022

Hilf uns dabei, eine weltumspannende Collage an Erfahrungsberichten zu Weisheitsthemen zu sammeln und miteinander ins Gespräch zu bringen.

Die Erde ist eine Scheibe. Zwei mal zwei macht vier. Viren gibt es nicht. Zucker kann Karies verursachen. Die Wirtschaften der Welt werden von einer unsichtbaren Hand zum größtmöglichen Glück aller gelenkt.

Wahrheiten und Unwahrheiten bestimmen unser Leben. Welche Wahrheiten sind überhaupt relevant? Welche Illusionen gefährden eine gelungene Lebensführung?

Der Tod ist groß.

Wir sind die Seinen

Lachenden Munds.

Wenn wir uns mitten im Leben meinen,

wagt er zu weinen

mitten in uns.

Liegt im Dao das Gute Leben verborgen? Wo muss ich es dann suchen? Was ist das Dao überhaupt?