Truth

“I can feel that my teeth are harder than my lips and my tongue.”

“If I don’t eat, and I don’t drink, I get weak.”

“When I try not to sleep for 24 hours, severe fatigue overcomes me. “

Everyone knows these simple truths. We gain bodily experiences that support them. And then there are other truths that can’t be acquired as easily.

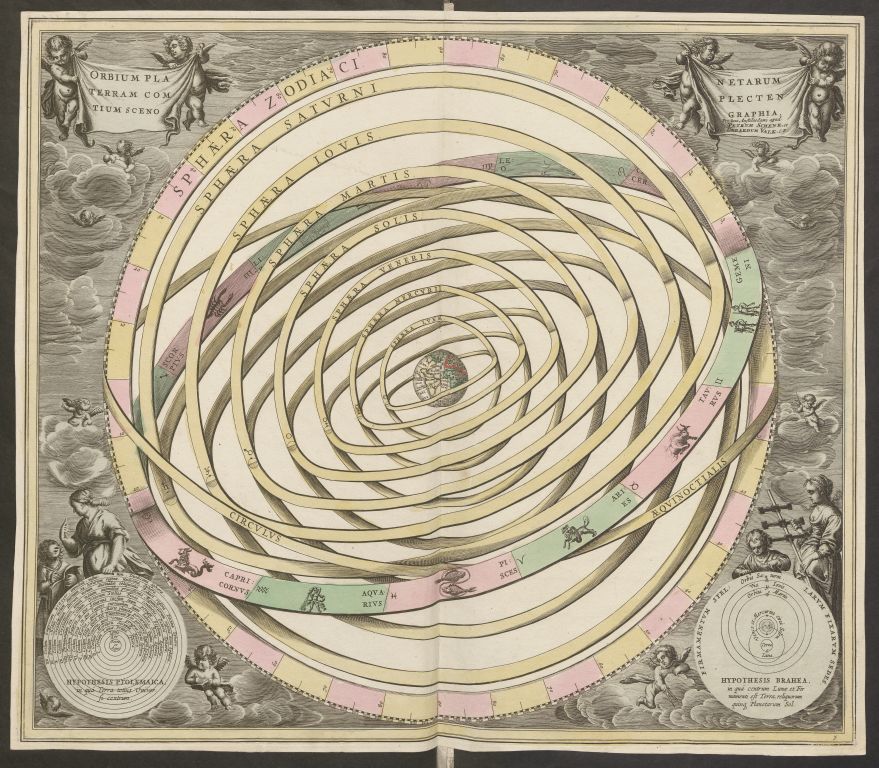

“The Earth is a sphere, revolving on its axis, and around the sun.”

“Many millions of years ago, different creatures existed on our planet than today.”

“Morphine is an effective painkiller.”

To see these truths, one must learn certain procedures: of geometry and celestial observation, of paleontology and pharmacy.

There are philosophical debates about the meaning of the word “truth”, whether it refers only to correspondence theories, to the absence of contradictions, to the open disclosure of a fact, or to the agreement between people. These debates, however, are largely idle. For there are all these forms of truth.

Sometimes truths are established by matching procedures, such as matching a fingerprint with the pattern on the skin of a finger. Other times, contradictions are ruled out, such as when testing a mathematical theory. Excavations by paleontologists bring hidden things to light. And when a jury must unanimously decide whether someone is guilty or not, their consensus makes it true that the defendant is guilty.

Truths are not always certain. Their certainty depends on the proceedings. It is hard to imagine that one day I will admit that my teeth are no harder than my tongue and lips after all. But it may be that a jury has erred, overruled by a higher court.

Scientific Revolutions

Modern sciences constantly face established knowledge sceptically. Because knowledge only exists where people refer to truths, this procedure often leads to the shattering of established truths. Absolute truths and final certainty are not the goal of modern enlightened science. It searches for errors, seeking evermore precision. Its greatest success consists in triggering a so-called revolution that shakes up an entire past body of knowledge. This happened, for example, when Copernicus shook the Ptolemaic view of the world, Lamarck and Darwin discovered the evolution of species, and Einstein proved the independence of space and time in Newtonian physics to be false. Despite the experience of these shocks, we can say that it is true that space is curved, and that species developed in a process of evolution. Modern physics after Einstein, and biology after Darwin have confirmed this via special methods. For the time being this is true.

Even beyond science, it can be more interesting and relevant to discover illusions and fallacies instead of truths. To believe that one gets through life without suffering, and does not have to die is an illusion. That technical progress would bring only advantages to people was an illusion.

It is good to lose illusions and to expose errors. To believe that one can get through life without suffering, and that one does not have to die, is bad. For then one easily falls into despair when confronted with suffering and death. It is better to prepare for these events. To bring forth technical innovation without reckoning with the fact that it may have unpleasant consequences for society is naïve and may lead to nasty surprises. It is better not to have an illusionary optimistic-ideological attitude towards technology, but rather a sober and realistic one.

For practical reasons, therefore, interest in debunking fallacies and illusions is important because they can backfire. Yet, there may also be, as Nietzsche thought, very useful illusions conducive to survival: so-called “life lies”. For example, when a person deludes themself (and others) about their ability to do something that is not seen as corresponding to reality. This illusion may make them feel cheerful and proud of themselves, which may benefit their social life in general—but self-overestimation can also lead to unpleasant surprises.

Enlightenment

One can call the process of discovering errors and illusions “enlightenment”. The ability to see error and abandon illusion can be seen as an aspect of wisdom. Contrarily, a person who holds on to errors and illusions when they should know better is a fool or a dreamer—and not wise. The humility of Socrates, who said of himself that he knew that he knew nothing, is also helpful in this sense. For it caused him to look to others for knowledge. What he found were errors and illusions. His interlocutors were not always pleased with being debunked. Nevertheless, it was probably helpful for them to be exposed by Socrates, as those who believe fallacies or falsehoods know little and may act on false premises. Wasn’t Buddha a similarly wise enlightener when he proclaimed: “There is suffering” and thus wanted to free people from the illusions of a life devoid of suffering?

There are many truths that may not seem relevant to our lives. The exact charge of anelectron, the age of the universe, the skull size of individuals of an extinct species of dinosaur—these all seem irrelevant to us (besides the fact that we exist as humans in the cosmos). But sometimes supposedly remote truths find applications in techniques. When Copernicus calculated the double motion of the earth, he could not have guessed the impact that would one day have on navigation or space travel. And truths about laser light, which also have to do with phenomena of quantum physics, did not at first seem to have any practical significance in everyday life. But they have led, among other things, to the CD player, which before the introduction of the storage of music on computers and MP3 players, was (and still is) of importance in the everyday life of many music lovers.

So the question of what the truths that really matter to our lives are, is difficult to answer. Trying to find out what truths one needs to know in order to become wise might therefore not be the right approach at all. Striving to lose as many illusions as possible might be more helpful. Perhaps the number of fallacies and illusions is inexhaustible. Therefore, a cautious and skeptical attitude toward truth claims seems prudent. According to one of the Pyrrhonian maxims, it is better not to claim anything to be true, as this only leads to disputes and unrest— and in this sense, Pyrrho (360-270 BC) can be regarded as a sage. Perhaps wisdom, then, has less to do with believing oneself in possession of certain life-relevant truths, than with shunning errors and illusions, being cautious in one’s claims to knowledge, and staying out of disputes as best as possible.

MH, Zürich 2022

Hilf uns dabei, eine weltumspannende Collage an Erfahrungsberichten zu Weisheitsthemen zu sammeln und miteinander ins Gespräch zu bringen.

Die Erde ist eine Scheibe. Zwei mal zwei macht vier. Viren gibt es nicht. Zucker kann Karies verursachen. Die Wirtschaften der Welt werden von einer unsichtbaren Hand zum größtmöglichen Glück aller gelenkt.

Wahrheiten und Unwahrheiten bestimmen unser Leben. Welche Wahrheiten sind überhaupt relevant? Welche Illusionen gefährden eine gelungene Lebensführung?

Der Tod ist groß.

Wir sind die Seinen

Lachenden Munds.

Wenn wir uns mitten im Leben meinen,

wagt er zu weinen

mitten in uns.

Liegt im Dao das Gute Leben verborgen? Wo muss ich es dann suchen? Was ist das Dao überhaupt?

Explore further album texts

Did you find yourself in the text?

TELL US YOUR IMPRESSIONS AND CRITICISM IN A COMMENT!

DON'T FORGET TO SEND US A SHORT ESSAY ON THE SUBJECT!

THE BEST ONES WILL BE PUBLISHED ON THE FRONT PAGE.

The Four Buddhist Truths

Old but Still Relevant

Origin

The Legend of the Four Sights says that Siddhartha Gautama, who later became Buddha, grew up as a prince in a royal palace. He was closely guarded by his father because all the astrologers and soothsayers kept predicting that his son would pass through the “Gate of Auspiciousness”. One day, when the prince expressed his desire to make an excursion, his father feared he might leave him and tried to make his place of residence as attractive as possible. The whole town was beautifully decorated. The streets were swept and strewn with fresh flower petals.

Despite all these precautions, the prince came across an old man, who was emaciated and in pain. His teeth had fallen out, his body was trembling and covered in wrinkles. The prince asked his charioteer: “Will each of us experience this fate? Tell me the truth!” The charioteer replied: “For all beings, old age overcomes youth. Even your father, your mother, your friends and relatives are not free from it.” In response, the prince said: “Only childish and ignorant beings don’t see what that means – proud and mad as they are in their youth.”

Some time later, on his next outing, the prince discovered a man on the road who was breathing with great difficulty. His skin was covered with sores and discolored; his senses weak and his body crippled. Again, the prince demanded an explanation. The charioteer replied: “This man is seriously ill. The splendor of his former health is gone, and he has no place of refuge.” The prince then compared health to a play in a dream and asked: “What wise person who has seen such a disease would still rate the play positively?”

On the next trip out, the prince saw a corpse on a bier, covered with a cotton cloth. He was surrounded by a group of relatives who were wailing and weeping with grief. As they followed the funeral procession, they pulled out their hair, threw dust on their heads and beat their chests. Whereupon the prince asked: “Who is this man being carried on the bier?” The charioteer replied: “This man has died. He must leave his possessions behind and will never see his wife, his children or his friends again.”

On his fourth and final exit, the prince noticed a peaceful-looking beggar on the road and wondered: “Charioteer, who is this quiet person with the offering bowl and saffron-colored clothes? The latter replied: “He is what we call a mendicant monk, a person who seeks peace, who has freed himself from attachments, and lives on alms.” [Lalitavistara Sutra, Ch.14, short version, www.84000.co]

These experiences shattered the young prince’s world view. Old age, illness and death showed him the inevitability of suffering; no wall could protect him from it. He vowed not to rest until he had recognized the cause of suffering. One of the following nights, he secretly left the palace, parted with his privileges and began to study the wisdom teachings of his time as an ascetic disciple. After a long journey through material and spiritual landscapes, he was convinced of having found the path to liberation.

Liberation

The Buddhist teaching is a possible answer to the question of how one should live, the question which – according to Kant – is at the heart of practical philosophy. However, it is also a therapeutic philosophy with a strong normative claim. The Four Noble Truths can be interpreted as diagnosis, etiology, prognosis, and prescription and represent a detailed guide to the liberation from suffering.

First Buddhist Truth

“Now this, monks, is the Noble Truth of dhukka: Birth is dukkha, aging is dukkha, death is dukkha; sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, & despair are dukkha; association with the unbeloved is dukkha; separation from the loved is dukkha; not getting what is wanted is dukkha. In short, the five clinging aggregates are dukkha.“

There are various interpretations of this text, but it is often associated with pessimism and an outdated ancient world view. In Factfulness (2018), Hans Rosling argues that pessimistic worldviews are characterized by unconscious prejudices. Despite all its imperfections, the world is in a much better state than we think [1a]. In his highly acclaimed publication Enlightenment Now (2018) Stephen Pinker uses statistics to postulate that security, peace and happiness are on the rise both in the West and worldwide. Is it possible to empirically test claims about humanity’s state of happiness? One problem is certainly that the people who suffer the most don’t take part in surveys. However, there is a new idea that is suitable to challenge the established statistics.

In 2022, Population Ethical Intuitions, a study by Lucius Caviola et al. was published, that examined what average Western citizens (in this case Americans) think about the evaluation of happiness and suffering. The result was astonishing. On average, the participants – unlike the classic utilitarians – thought that a world is worth living in only, if there are significantly more happy than suffering people. In other words: they gave more weight to suffering than to happiness. Were the participants aware of what this means for their own world? If this asymmetry is applied to the best-known survey on life satisfaction, the World Happiness Report, then the overall assessment is negative [1b]. Perhaps the early Buddhist denial of the world (samsara) is not so outdated after all, at least if the evaluation is based on empathy [1c].

Second Buddhist Truth

“And this, monks is the noble truth of the origination of dukkha: the craving that makes for further becoming – accompanied by passion & delight, relishing now here & now there – i.e., craving for sensual pleasure, craving for becoming, craving for non-becoming.“

The second Buddhist truth is more than a reflection on the functioning of the psyche. It describes the driving force of the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. In his book River Out of Eden (1995), Richard Dawkins uses the (controversial) metaphor of God’s utility function when he talks about this force. This refers to the struggle of organisms to maximize the proliferation of their genes. Evolutionary selection has shown that the ability to suffer improves biological fitness. The intensity of pain sensations and the depth of suffering therefore increase in the course of evolution [2a]. We do not (yet) know whether this trend can be reversed by technological and social progress [2b]. It could also be that visions of secular salvation (paradise engineering) serve a similar social function as religious promises of salvation. They make the suffering in the present more bearable and postpone happiness into the future [2c].

“God’s utility function” is also a cause of the population growth in recent decades. The absolute number of suffering people is greater today than at any other time in history up to the 20th century. The number of happy people is greater as well, but the suffering of some cannot simply be compensated with the happiness of others [2d]. Why does the second Buddhist truth not clearly name procreation as the prime avoidable cause of human suffering? One possible answer can be found in the context of the third Buddhist truth.

Third Buddhist Truth

“And this, monks, is the noble truth of the cessation of dukkha: the remainderless fading & cessation, renunciation, relinquishment, release, & letting go of that very craving.“

The third Buddhist truth says that suffering can be defeated by recognizing and eliminating its cause (tanha, craving). Isn’t the most obvious conclusion to eliminate the desire to have children and thus prevent the next generation from suffering? What seems trivial to us today was not obvious to the early Buddhists. Despite the parallels between the doctrine of rebirth and (epi-)genetics there is a crucial difference. Buddhists assumed that a stream of consciousness exists that passes into the next existence at the moment of death (and not at the moment of procreation). The possibility that the consciousness of the child goes back to the consciousness of the parents was also discussed (!) but rejected because children with the same parents develop different cognitive characteristics [3a].

Given the above assumptions, it is plausible that the Buddhists paid particular attention to the transition from life to death. It is also understandable that they regarded self-dissolution in meditation as a kind of exercise for the dying process. According to the Nirodha interpretation of the Pali Canon Buddha was convinced that the highest state of meditation (Pari-nirvāṇa) – achievable only in death – is the key to the cessation of rebirths, and therefore the key to the cessation of suffering. In some traditions, this end is interpreted as the dissolution of individual consciousness into a cosmic consciousness [3b] [3c].

Regardless of the ancient soteriology, Buddhist meditation can be perceived as a profound inner liberation. The positive experience of non-existence (of the self) is the key to cope with transience and death [3d]. Buddha describes the self as a composite, dependent and changeable phenomenon (anatta). We should be able to view it with the same equanimity as all other phenomena in this world [3e]:

“This is what you should think of all this fleeting world:

a star at dawn,

a whirl in a stream,

a flash of lightning in a summer cloud,

a phantom of a dream.”

Fourth Buddhist Truth

“And this, monks, is the noble truth of the way of practice leading to the cessation of dukkha: precisely this Noble Eightfold Path: right view, right resolve, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration.”

The Eightfold Path is directed towards a way of life that supports meditation:

- Wisdom (prajna) justifies the path: right view and resolve.

- Ethical behavior (sila) fosters a favorable environment: right speech, action, and livelihood.

- Mental discipline (samadhi) creates the preconditions for spirituality: right effort, right mindfulness and concentration.

Although the connection between procreation and the emergence of a new consciousness was not properly recognized, the ideal of childlessness applied to monks. They justified their attitude with the attachment to the material world (samsara) which is inherent in parenthood, and which subsequently jeopardizes the meditative goal. It is true that such a strict interpretation of the Eightfold Path would put a definitive end to human suffering. In practice, however, most people were (and still are) overburdened by such strictness. From the very beginning, Buddhism developed through a symbiosis of monks and sympathizing laypeople. While the monks preserved and taught the knowledge, the lay community kept it alive. There are good reasons to believe that early Buddhism influenced the Hellenistic philosophers, especially the Cynics, Pyrrho, Epicurus and the early Stoics [4a]. In the present time, related ideas can be found in movements such as simple living, back-to-nature, deep ecologyand antinatalism [4b] [4c].

In the 1st century BC, a branch (Mahayana) emerged in Buddhism that upgraded compassion relative to wisdom. Reflections on the contingency and impermanence of the self (anatta) had led to the conclusion, that the suffering of others is just as real and important as one’s own suffering. The new ideal (bodhisattva) was now a person who renounces his/her own salvation to free others from suffering [4d]. In the Human Genome Project (1990-2003) the Buddhist idea of a profound connection between all humans finally found a scientific correspondence: 99.9% of the human genome are permanently being reborn [4e].

Today, an upgrading of compassion corresponding to the Mahayana-movement can be found in suffering-focused ethics, an umbrella term, which includes secular Buddhism and negative utilitarianism, among others [4f] [4g]. With the intensified exchange between Western and Eastern philosophy, the boundaries of Buddhism have become fluent.

The non-dogmatic Buddha

2500 years ago, when Buddha was wandering around with a large community of monks, he encountered great skepticism in a town called Kesaputta. The inhabitants of this town, called Kalamas, complained about the multitude of controversial teachings: “There are some monks and Brahmins, venerable sir, who visit Kesaputta. They explain and expound only their own teachings; the teachings of others they despise, revile and tear apart. Venerable sir, there is doubt, there is uncertainty within us. Which of these venerable monks and brahmins has spoken the truth and which has spoken falsehood?”

Buddha was probably a rhetorical talent and had the ability to adapt his language to the audience. In this case he replied as follows: “It is right for you, Kalamas, to doubt, to be uncertain. Do not rely on what has been acquired through repeated hearing, nor on rumor, nor on what is written in a scripture, nor on reasoning such as: The monk is our teacher. Kalamas, if you yourselves know: These things are bad, these things lead to harm and evil, then give them up. But if you yourselves know that these things are good, then enter them” [Kalama Sutta, short version, www.accesstoinsight.org].

It was only after this introduction that he began to explain his teachings, using examples from real life. This is a plea for independent thinking, for the examination of assertions and for the value of experience. The non-doctrinaire Buddha appears here as a harbinger of the Socratic way of thinking.

Source: Socrethics, February 2025

Zurich, Bruno Contestabile